This document is designed to assist readers in understanding the information presented in HANZAB. It consolidates the explanatory information from the introductions of all seven volumes (for the original text, see introductions for Vol. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7) along with information about changes in presentation in the HANZAB website. For lists of the species included in each volume of the HANZAB books see the contents for each volume: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7.

NOTE: Threats and Human Interactions was not included as a separate section in volumes 1 to 4 of the books. For consistency, this heading has been added to these entries and links to relevant text within the entries created. Conservation Status has also been added. New distribution maps have been added to some species but links to the original maps have been included below the new map. Research published after the HANZAB book are included in the Bibliography.

Website presentation changes

The move to a website has allowed a number of changes to the presentation:

- some paragraphs have been split to make them more readable.

- reference below to first paragraph, second paragraph etc may not be correct

- hyperlinks have been added

- links to external site annotated with

- hyperlinks to broken links being removed but text retained (process of identifying broken links underway – R2.0)

- Other English names altered to better support search by fully stating species names rather than grouping them

- taxonomic changes and changes to the content of entries documented

TAXONOMY AND NOMENCLATURE

The taxonomy has been updated using AviList 2025 for orders, families and species. Subfamilies are not included in AviList 2025 but are flagged for future releases. Subfamilies have been retained as per the HANZAB 2023 but see notes in the family entry for issues raised by changes to the taxonomic sequence of species (eg Anatidae). Subspecies, although included in AviList 2025, have not been finalised. Species split or merged in AviList 2025 have the subspecies changed. Notes about inconsistencies at the subspecies level are included in the species Taxonomic Changes.

Nomenclature of orders, families and species in the HANZAB books has been updated using the following sources:

- AviList 2025

- Working List of Australian Birds (Birdlife Australia Version 4.1 and 4.3), referenced as WLAB 4.1 and WLAB 4.3;

- Checklist of the Birds of New Zealand, Fifth Edition, 2022 (Ornithological Society of New Zealand) referenced as NZCL 2022;

- Birdlife International datazone website for species recorded in Antarctica, French Southern territories, Heard and MacDonald islands, Bouvet Island, and South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (Accessed 10 June 2025); and

For HANZAB 2023 the following sources were also used:

- Birdlife International datazone website for species recorded in Antarctica, French Southern territories, Heard and MacDonald islands, Bouvet Island, and South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands (Accessed 23 March 2023); and

- for extralimital subspecies, HBW and BirdLife International (2022) Handbook of the Birds of the World and BirdLife International digital checklist of the birds of the world. Version 7. Available at: https://datazone.birdlife.org/userfiles/file/Species/Taxonomy/HBW-BirdLife_Checklist_v7_Dec22.zip, referenced as BLI 2022.

Where the treatment varies between these sources, it may be noted by comments in the text or by presenting each variation with comments. Eg. subspecies cooki of Red-fronted Parakeet Cyanoramphus novaezelandiae in WLAB 4.1 is elevated to species level (Norfolk Island Parakeet Cyanoramphus cookii) in NZCL 2022. See Taxonomic changes since HANZAB book published in Red-crowned Parakeet (the NZCL 2022 name for Red-fronted Parakeet) or HANZAB Index+ for the treatment adopted.

[Information from Volumes 1, 3, 4 and 5,6,7]

From Vol. 1

The arrangement and nomenclature of orders, families and species closely follows those of Condon in the Checklist of the Birds of Australia, Part 1 (1975), and of Kinsky in the Annotated Checklist of the Birds of New Zealand (1970), both of which are essentially those of Peters’ Checklist of Birds of the World, Volume 1 (1979), and that in itself is much the same as the Wetmore order of 1960. At the generic level, admitted to be the most arbitrary, controversial and mutable taxon in the system, we have avoided sub-genera for the most part and thus differ from the above standards in one way or another. In some genera (Pterodroma, Sula and Phalacrocorax), we do so because proposed sub-genera seem not yet to be widely accepted; in Ardea, because the proposed sub-genera are hard or even impossible to separate. Further, we have treated some isolated, sedentary and insular forms of shags and ducks as full species rather than as subspecies because that seems to be more sensible biologically. Preparation of our first volume has coincided with the preparation of the Catalogue of Australian birds for the Australian Biological Resources Survey (ABRS) by Dr R. Schodde, and of the third edition of the New Zealand checklist. Originally we hoped that both would be published well before our first volume, but in the event we were obliged to commit ourselves taxonomically before they appeared. Thus, in spite of full cooperation and help from the compilers of these works and their helpers, we cannot be sure that our arrangement and those of the ABRS list and the new New Zealand checklist will be the same. Sibley, Ahlquist and Monroe (Auk 105: 409-23) have recently proposed a new classification of birds based on DNA-hybridization. Whether or not this comes to be generally accepted, it came too late for us to use. To have done so would have meant scrapping much work and preparation, and delaying production intolerably.

Names of the birds in Dutch, French, German, Japanese, Malay, Maori and Russian, as far as they are available, are listed in an appendix at the end of the book. There is also a separate appendix for Aboriginal names. The official attitude of the RAOU to the use of English names is set out in the Supplement to Emu 1977, Vol. 77 (Recommended English Names for Australian Birds). It favours an international rather than a parochial or insular approach to the matter and we have done so throughout. We have departed from the Recommended English Names in two cases: we have used Salvin’s Prion for Pachyptila salvini (in place of Lesser Broad-billed Prion; see explanation in masthead of P. salvini) and Australian White Ibis (in place of Sacred Ibis) for Threskiornis molucca, which we have considered a separate species. English names for species endemic to New Zealand are usually taken from the Annotated Checklist of the Birds of New Zealand (Kinsky 1970) and amendments (Notornis 27, Suppl.).

From Vol. 3

NOMENCLATURE

The taxonomy, nomenclature and arrangement of orders, families and species in Volume 3 follow those of the revised species list of Australian birds by Christidis & Boles (1994), except for the position Of the Scolopacidae within the Charadriiformes. This exception became unavoidable with the split of the Charadriiformes between Volumes 2 and 3, and because work on Volume 2 was too advanced to follow Christidis & Boles (1994) fully, Following Christidis & Boles (1994), the sequence of families Of Charadriiformes that occur in the HANZAB region is: Pedionomidae, Scolopacidae, Rostratulidae, Jacanidae, Chionididae, Burhinidae, Haematopodidae, Recurvirostridae, Charadriidae, Glareolidae and Laridae. In Our sequence, the Scolopacidae are out of place.

In this Volume, the taxonomic ranking given to the groups that comprise the Laridae follows Christidis & Boles (1994), but differs from that given in the introduction to the Charadriiformes in HANZAB 2.

English names for birds of Australia and Australian territories follow those ofChristidis & Boles ( 1994); English names for species endemic to New Zealand follow those of NZCL (1990).

Botanical names In the Laridae and Columbidae, the names of plants in all sections other than Food were checked by G. Carr using the following authorities:

- Allan, H.L. 1961. Flora of New Zealand. 1. R.E. Owen, Gov’t Printer, Wellington.

- Australian Biological Resources Study. 1993. Flora Of Australia. 50. Oceanic Islands. AGPS, Canberra.

- Hnatiuk, R.J. 1990. Census of Australian Vascular Plants. Aust. Flora & Fauna Ser. II; Bureau Flora & Fauna. AGI’S, Canberra. Moore, L.B., & E. Edgar. 1970. Flora of New Zealand. 11. A.R, Shearer, Gov’t Printer, Wellington.

- Wallis, J.C., & H.R. Airy Shaw. 1973. A Dictionary of the Flowering plants and Ferns. Cambridge Univ. press, Cambridge.

From Vol. 4

TAXONOMY AND NOMENCLATURE

As in Volume 3, we continue to follow the arrangement and nomenclature of Christidis & Boles (1994) and amendments (Christidis & Boles In press). For details of subspecies and subspecific nomenclature, we have followed Schodde & Mason (1997) where it was available except in cases where it conflicted with species limits set out in Christidis & Boles (1994, In press). Any deviations from the taxonomy of Schodde & Mason (1997) are explained within the texts. The arrangements of the few species recorded in the wider HANZAB region that were not included within these publications were determined in consultation with L. Christidis & W.E. Boles, as members of Birds Australia’s Taxonomic Advisory Committee, based on the principles and sources used by them in compiling their 1994 publication. English names follow those of Christidis & Boles (1994); English names for species endemic to NZ follow those of OSNZ (1990).

REFERENCES

- Christidis, L., & W.E. Boles. 1994. The Taxonomy and Species of the Birds of Australia. RAOU Monogr. 2. RAOU, Melbourne.

- —, — In press. Emu.

- OSNZ (Ornithological Society of New Zealand) . 1990. Annotated Checklist of New Zealand Birds and the Ross Dependency, Antarctica. Third edn. Random Century, Auckland.

- Schodde, R., & I.J. Mason. 1997. Zoological Catalogue of Australia. 37.2. Aves. CSIRO Publ., Melbourne.

From Vol. 5, 6 and 7 (repeated in each volume)

TAXONOMY AND NOMENCLATURE

Birds

The publication of the ground-breaking Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines by Schodde & Mason (2000 [abbreviated throughout this volume as DAB]) has provided a substantial base from which to further investigate the variation in species and, of greater import, the subspecies of Aust. birds, and has greatly assisted us in the preparation of this volume. For the first time in contemporary ornithology in the Aust. region, DAB presents a complete listing and analysis of the terminal taxa of Aust. passerine birds.

As in Volumes 3 and 4, for families and species we continue to follow the arrangement and nomenclature of Christidis & Boles (1994) and amendments (Christidis & Boles In prep.); the latter will incorporate several changes published in DAB. The departures from Christidis & Boles (1994) recognized in this volume are: separation of Short-tailed Grasswren Amytornis merrotsyi from Striated Grasswren A. striatus; recognition of Kalkadoon Grasswren Amytornis ballarae as a species separate from Dusky Grasswren A. purnelli; and separation of Western Wattlebird Anthochaera lunulata from Little Wattlebird A. chrysoptera. In this and subsequent volumes, details of subspecies and subspecific nomenclature essentially follow DAB except in cases where it conflicts with species limits set out in Christidis & Boles (1994, In prep.). However, even in those instances, subspecific treatment of DAB is always discussed within the texts and reasons for departure from DAB are given.

The arrangements of the few species recorded in the wider HANZAB region that were not included within the above publications were determined in consultation with L. Christidis and W.E. Boles (representing Birds Australia’s Taxonomic Advisory Committee and a member of the HANZAB Steering Committee), based on the principles and sources used by Christidis & Boles in compiling their 1994 publication. For NZ species, scientific nomenclature follows OSNZ (1990) except in cases where it conflicts with Christidis & Boles (1994, In prep.).

English names follow those of Christidis & Boles (1994); English names for species endemic to NZ follow those of OSNZ (1990).

Plants and animals other than birds

All scientific names, other than those of birds, were checked against the following references; for those groups for which volumes have been published, we have used the multi-volume series the Flora of Australia, the Fauna of Australia and the Zoological Catalogue of Australia.

Plants

For Aust., Hnatiuk (1990), ABRS (1993) and, for specific families, George (1986, 1989), Chippendale (1988) and Orchard (1995, 1998); for NZ, Allan (1961), Poole & Adams (1963), and Moore & Edgar (1970); and, more generally or outside these areas, Wallis & Airy Shaw (1973). We have retained Eucalyptus as a single genus, though we have often placed the subgeneric name Corymbia in brackets after Eucalyptus for species of bloodwoods.

Animals

- GENERAL INVERTEBRATES: Marshall & Williams ( 1972).

- MOLLUSCS: Vaught (1989) .

- SPIDERS: Main et al. (1985).

- INSECTS: Taylor et al. (1985); Lawrence et al. (1987), Campbell et al. (1988), Common (1990), CSIRO (1991), Naumann (1993), Lawrence & Britton (1994) and Nielsen et al. (1996) .

- FISH: Paxton et al. (1989) , Eschmeyer (1990) and Gommon et al. (1994).

- AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES: Cogger et al. (1983 ) and Cogger (1992).

- MAMMALS: Bannister et al. (1988) and Strahan (1995).

REFERENCES

- Allan, H.L. 1961. Flora of New Zealand. I. R.E. Owen, Govt Printer, Wellington.

- ABRS (Aust. Biol. Resources Study). 1993. Flora of Australia. 50. Oceanic Islands. Aust. Govt Pub!. Service, Canberra.

- Bannister, J .L. , et al. 1988. Fauna of Australia. 5. Mammalia. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Campbell, I., et al. 1988. Zoological Catalogue of Australia. 6. Ephemeroptera, Megaloptera, Odonata, Plecoptera, Trichoptera. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Chippendale, G.M. 1988. Flora of Australia. 19. Eucalyptus, Angophora (Myrtaceae). Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Christidis, L., & W.E. Boles. 1994. RAOU Monogr. 2.

- Cogger, H.G. 1992. Reptiles and Amphibians of Australia. Rev. edn. Reed, Sydney.

- —, et al. 1983 . Zoological Catalogue of Australia. 1. Amphibia and Reptilia. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Common, I.F.B. 1990. Moths of Australia. Melb. Univ. Press, Melbourne.

- CSIRO. 1991. Insects of Australia. CSIRO Publ., Melbourne.

- Eschmeyer, W.N. 1990. Catalogue of the Genera of Recent Fishes. Calif. Acad. Sci. , San Francisco.

- George, A.S. (Ed.) 1986. Flora of Australia. 46. Iridaceae to Dioscoreaceae. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- — 1989. Flora of Australia. 3. Hamamelidales to Casuarinales. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Gommon, M.F. , et al. (Eds) 1994. The Fishes of Australia’s South Coast. State Printer, Adelaide.

- Hnatiuk, R.J. 1990. Census of Australian Vascular Plants. Aust. Flora & Fauna Ser. 11 (Bureau Flora & Fauna): Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Lawrence, J.F. , & E.B. Britton. 1994. Australian Beetles. Melb. Univ. Press, Melbourne.

- —, et al. 1987. Zoological Catalogue of Australia. 4. Coleoptera. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Main, B.Y., et al. 1985. Zoological Catalogue of Australia. 3. Arachnida. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Marshall, A.J. , & W.O. Williams. 1972. Textbook of Zoology: Invertebrates. Macmillan, Melbourne.

- Moore, L.B., & E. Edgar. 1970. Flora of New Zealand. II . A.R. Shearer, Govt Printer, Wellington.

- Naumann, I. 1993. CSIRO Handbook of Australian Insect Names. CSIRO Publ., Melbourne.

- Nielsen, E.S., et al. 1996. Checklist of the Lepidoptera of Australia. Monographs on Australian Lepidoptera, Vol. 4. CSIRO Publ., Melbourne.

- Orchard , A.E. (Ed.) 1995. Flora of Australia. 16. Elaeagnaceae, Proteaceae 1 . CSIRO Publ., Melbourne.

- — 1998. Flora of Australia. 12. Mimosaceae (excluding Acacia), Caesalpiniaceae. CSIRO Publ., Melbourne.

- OSNZ (Orn. Soc. of NZ [E.G. Turbon, Convenor, Checklist Committee]). Checklist of the Birds of New Zealand and the Ross Dependency , Antarctica. Third edn. Random Century, Auckland.

- Paxton, J.R., et al. 1989. Zoological Catalogue of Australia. 7. Pisces. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Poole, A.L., & N.M. Adams. 1963 . Trees and Shrubs of New Zealand. R.E. Owen, Govt Printers, Wellington.

- Schodde, R., & I.J. Mason. 2000. Directory of Australian Birds: Passerines. CSIRO Publ., Melbourne.

- Strahan, R. (Ed. ) 1995. The Mammals of Australia. Reed New Holland, Sydney.

- Taylor, R.W., et al. 1985 . Zoological Catalogue of Australia. 2. Hymenoptera. Aust. Govt Publ. Service, Canberra.

- Vaught, K.C. 1989. A Classification of the Living Mollusca. Am. Malacologist Inc., Melbourne, Florida.

- Wallis, J. C., & H.K. Airy Shaw. 1973 . A Dictionary of the Flowering Plants and Ferns. Cambridge Univ. Press, Cambridge.

TREATMENT AND PRESENTATION

[Information from Volumes 1 and 5]

From Vol. 1

The bulk of the book is set out in standard systematic form with brief introductory remarks for taxa above the level of genus, written from the point of view of Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica, and detailed accounts for each species. The introductions for orders characterize the sorts of birds concerned, list constituent families and outline taxonomic arrangements that differ from ours. This may be transferred to the introduction for a family where there is only one family in the order. Introductions for families usually cover the types of birds concerned, number of sub-taxa and informal groupings such as superspecies, world distribution and representation in our region, and chief morphological and behavioural characters. Below the level of species we have avoided as far as possible any treatment of subspecies except in the paragraph for Geographical Variation at the end of the Plumages section. Subspecific discrimination is a valuable and necessary tool in museum studies and with birds in the hand, but not generally in the field.

The species accounts are divided into sections for Field Identification, Habitat, Distribution, Movements, Food, Social Organization and Behaviour, Voice, Breeding, and Plumages and related matters. If information on population is available it is included in the section on Distribution. The original plan was to have an editor for each section and to solicit an account for each species from experts, which the editors would then treat for consistency of style, arrangement and presentation. This simply did not work. For various rear sons, some of those who originally agreed to be editors could not carry on through the long period of preparation, and many contributors could not meet our onerous demands. Many ad hoc reorganizations had to be made and so we cannot give a simple list of editors and contributors. Detailed acknowledgements are made below. Details of the scope of each section, with an explanation of conventions and abbreviations used and special problems, are discussed in separate introductions for each section below. Some abbreviations and conventions are used throughout the work; others apply only to a particular section. The general ones are explained separately (see Abbreviations and Conventions).

About 900 species of birds have been recorded within our limits, depending somewhat on the classification used and including vagrants, introduced species with viable feral populations, and those extinct within historical times. In this volume we cover 196 species, of which most (162) breed within our limits and so receive full treatment in ten sections, as mentioned above. Many pelagic and Antarctic birds are, of course, rare and seldom found in Australian and New Zealand waters but breed in Antarctica or on subantarctic islands. Others (27) are regarded as non-breeding visitors, vagrants or accidentals, though some could be more regular migrants annually to Australian or New Zealand seas or to little-known areas on land. For them, sections on Food, Social Organization and Behaviour, Voice and Breeding are omitted, as may be detailed descriptions of plumage if material for study was not available (however, some very recent occurrences or vagrants to Antarctica or subantarctic islands have only a short paragraph). All these breeding and non-breeding species and most vagrant species are illustrated in colour, to show the plumages that can be identified in the field, from downy young to breeding adult. Further, there are seven species that are extinct in historical times or that have not been recorded since 1900 or for which we think that the record is doubtful, definitely erroneous or otherwise unacceptable. These are not illustrated and have only a short paragraph, setting out the evidence. Fossil and subfossil species are not covered.

From Vol. 5

The bulk of the book is set out in standard systematic form with brief introductory remarks for taxa above the level of genus, written from the point of view of Australia, New Zealand and Antarctica (see description of the HANZAB region below), and detailed accounts for each species. The only order introduction in this and subsequent volumes, for the Passeriformes, characterizes the sorts of birds within the Order, lists the constituent families in the HANZAB region and outlines taxonomic arrangements that differ from ours. A few morphological and behavioural characters common or frequent in the Order are also summarized. Introductions for families usually cover the types of birds concerned, number of sub-taxa and informal groupings such as superspecies, world distribution and representation in our region, and chief morphological and behavioural characters common or frequent in the family. Some aspects of behaviour, such as resting postures, comfort behaviour, including head-scratching, bathing and preening, and thermoregulation are characteristic of whole families rather than of individual genera or species; they are discussed or mentioned here rather than in the species accounts where they do not fit in easily and would need to be repeated time and again.

The species accounts are divided into sections for Field Identification, Habitat, Distribution and Population, Threats and Human Interactions, Movements, Food, Social Organization, Social Behaviour, Voice, Breeding, and Plumages, Bare Parts, Moults, Measurements, Weights, Structure and Geographical Variation; in some circumstances, additional sections for Ageing, Sexing and Recognition follow Structure. Each account concludes with a fu ll list of references. Throughout the work, detailed descriptions and summaries are largely confined to data collected in the HANZAB region (see below) and extralimital data are not usually presented in any detail, though important useful references are cited . We do, however, present a little more detail from New Guinea sources where there is little or no information for Australia or New Zealand. Details of the scope of each section, with an explanation of conventions and abbreviations used and problems specific to those sections, were discussed fully in introductions for each section in Volume 1 and revised introductions for most sections appear below.

Breeding species receive full treatment in these sections. For non-breeding migrants, the sections on Social Organization, Social Behaviour and Breeding are omitted. For species that are accidental to the HANZAB region , only the sections on Field Identification, Habitat, Distribution, Movements and Plumages and related matters are covered. In these categories, some species, such as introduced species, may have a reduced treatment for Plumages and related matters if there is an adequate summary published elsewhere (see the introduction to Plumages and related matters). For species that have become extinct since European settlement, we summarize as much as we know of the biology of the species, and prepare as full an account for Plumages and related matters as possible with the material available in museums or elsewhere. However, for many extinct species, there is little or no information on the biology of the birds and few specimens available to us, so we have been able to do little.

Lastly, some species receive only a brief treatment, with a summary paragraph outlining the occurrence or claimed occurrence in the HANZAB region. Such species include: vagrants to the wider region covered in HANZAB but beyond the generally recognized limits of Australia and New Zealand and their territories (for example, in this volume, two species vagrant to South Georgia from the Americas ); unverified reports or claims for the region; and failed introductions to the HANZAB region. Where there are many failed introductions within a family, they may all be dealt with together.

Some abbreviations and conventions are used throughout the work; others are applied only to a particular section. All abbreviations and conventions are listed [see Abbreviations and Conventions]. The rest of this introduction largely uses those abbreviations and conventions.

THE HANZAB REGION

The region covered by HANZAB is: Aust. within the limits of the Continental Shelf, including the reefs and islands of the Coral Sea, N to 10 S or the Qld-New Guinea political border, whichever lies farther N, but excluding the e. end of New Guinea and adjacent islands above 10 S; the Aust. external territories of Cocos-Keeling, Christmas (in the Indian Ocean)l, Lord Howe, Norfolk, Heard and Macquarie Is; NZ and its islands, from the Kermadec Grp in the N to Campbell I. in the S and the Chatham Grp in the E; the Antarctic Continent; and the subantarctic islands, ncluding Marion, Prince Edward, Iles Crozet, Iles Kerguelen, the islands of the Scotia Arc: South Georgia, South Sandwich, South Orkney and South Shetland Is, and the subantarctic territories of Aust. and NZ already mentioned. The boundaries of the region are shown on the various maps. [see Gazetteer]

FIELD IDENTIFICATION

[Information from Volumes 1, 3 and 4]

From Vol. 1

This section sets out the characters by which a species may be identified in the field, even without the help of illustrations. It goes without saying that the recognition of many features often or usually depends on the circumstances and wear of plumage, especially for birds at sea, and this should be kept in mind when making and evaluating observations. For the most part we have not presented differences between subspecies here, because we do not wish to encourage the idea that sub-species can be identified in the field, except in the case of a few, very well-marked examples. References are not usually given in this section.

[Note the mention of paragraphs here may not be appropriate as some may have been broken into multiple paragraphs in the online version.]

The presentation is in four paragraphs. The first is designed to help those who are ignorant of A’asian birds, or even of birds in general, to decide whether they are on the right track for identification. It gives a rough indication of the size, shape, appearance and type of bird being described. Measurements of total length, wingspan and weight are given in gross terms, as a guide to the size of the bird, and, where necessary with a broad indication of the proportions of head and neck, body and tail (detailed measurements are in the Plumages section). Brief mention is then made of outstanding characters of plumage or other features, especially if they are diagnostic, and it is indicated whether differences occur by age, season or sex.

The second paragraph (DESCRIPTION) describes the various stages of plumages as seen in the field. Here, as necessary, descriptions are given of adult male and female, breeding and non-breeding, downy young, juveniles and immature stages, as well as morphs and phases. After the first mention of a character, it is not usually repeated, only the differences being emphasized. It is hoped that with this information on the different stages in plumage, field observers will be encouraged to discriminate more carefully between sexes and ages than is often done, because important data on patterns of movement, age at first breeding and social behaviour can thus be collected.

The third paragraph (SIMILAR SPECIES) sets out those species that may be confused with the species in question, sometimes even to a point that may seem ridiculous or impossible. Field conditions, however, can play some strange tricks and one must be careful. There is nothing worse than publishing a doubtful or incorrect identification as a certainty, which will be perpetuated and is hard to eradicate or correct (see discussion in Distribution introduction). Some care has been taken to make comparisons between species in the same way: species X, Y or Z always first, smaller, paler, etc, than species A, which is the subject of the account.

The fourth paragraph tries to give an outline of less concrete aspects of identification and is generally the weakest part of the section. It is not easy to remember to record aspects of habitat, gait, swimming, flight and so on, which one assumes are perfectly obvious and well known. There is probably much scope for improvement here, because contributors and editors had a good deal of trouble in covering the field, even as a general outline. Usually fuller information (and references) on various aspects discussed here may be found in other sections. It has been thought necessary to condense substantially the very detailed descriptions and comparisons submitted by some contributors for the second and third paragraphs. It is hoped that such condensation has not gone too far and that nothing really important has been left out.

From Vol. 3

FIELD IDENTIFICATION

The approach to this section remains much as outlined in the Introduction to Volume 1, though several aspects deserve explanation or comment.

For paragraph one, it was difficult to obtain accurate values for length and wingspan and to establish relative size within genera or families. Published data vary greatly and, in some cases, we had considerable doubts about the accuracy of published data (e.g. the wingspans for many Charadriiformes given in Volumes 3 and 4 of BWP appear consistently too high). Whenever good data from museum specimens were available for birds collected in the HANZAB region, we used these in preference to published data. Otherwise, data were taken mainly from the following sources. WADERS: BWP (Volumes 3, 4); Hayman et al. (1986); Chandler (1989) and Paulson (1993); SKUAS, JAEGERS, GULLS AND TERNS: mainly Harrison (1983, 1987), BWP (Volumes 3, 4), and Olsen & Larsson (1995); COLUMBIFORMES: Frith (1982), Crome & Shields (1992), Pizzey (1980) and Slater et al. (1989). For relative size within genera or families, we relied entirely on information in the foregoing literature; Paulson (1993) proved particularly useful for many of the waders, as did Olsen & Larsson (1995) for the terns. In light of the difficulties encountered during preparation of this and previous volumes, we strongly encourage museum workers and others to help obtain and make available accurate measurements of length, wingspan and weight for A’asian birds, which would be invaluable for use in

future volumes of HANZAB.

Species accounts

The Charadriiformes present considerable difficulties in identification and ageing in the field. Fortunately, recent years have seen the appearance of a wealth of detailed specialist identification papers and guides covering waders, gulls and other groups, and many field identification problems previously considered almost impossible to resolve (e.g. separation of stints in juvenile plumage) are now possible

or even routine in some instances. Resolution of these difficult identification problems has come about largely through adoption of the so-called ‘new approach’ to identification (see Grant & Mullarney 1989), with its emphasis on topography and moult of birds as well as traditional skills of bird identification. With widespread use of telescopes and specialist identification guides, birdwatchers are nowadays scrutinising birds more closely than ever before and in much greater detail, as they attempt not only to identify a bird to species but also to determine its age, sex and stage of moult where possible. We have attempted to summarize all characters important in identification, ageing and sexing. The sections of Plumages and related matters are complementary to the Field Identification section and need to be consulted for more detailed information on patterns of individual feathers and of moult. An exception is made for those few very rare vagrant species where only a brief Plumages account is given (usually only when extralimital summaries are already available, e.g. in BWP); in these cases, the Field Identification accounts are more detailed than is normally the case. We have occasionally provided references for some particularly difficult identification problems. For a full review of the new identification techniques, plumages, topography, judgement of size and structure and other aspects of the new approach, see Grant & Mullarney (1989).

GLOSSARY

Some terms have been introduced into the accounts or have been used again but were not previously defined.

- APICAL SPOT: white tips of primaries of gulls.

- CARPAL BAR: band of dark feathers extending diagonally across the inner upperwing, from the carpal joint to the base of the tertials, and contrasting with paler rest of wing; formed by median secondary coverts and rear rows of lesser secondary coverts. Characteristic of many gulls.

- COMMIC TERNS: a group of very similar medium-sized Sterna terns: Roseate S. dougallii, White-fronted S. striata, Common S. hirundo, Arctic S. paradisaea, Antarctic S. vittata and Kerguelen S. virgata.

- CUBITAL BAR: band of dark feathers along the leading-edge of the inner upperwing, and contrasting with paler rest of wing; formed by lesser secondary coverts. Occurs in many terns.

- HOOKBACKS: dark markings on the outer primaries of some terns, in which dark areas on tips of the outer webs extends on to the inner webs as a dark line along inner edge; see illustrations Fig. 8, Antarctic Tern.

- INNERWING-COVERTS: Secondary coverts. In this volume, used mainly to refer to those coverts visible on the folded wing of a standing bird.

- INNERWING: secondaries and secondary coverts (including tertials and their coverts).

- LINING OR WING-LINING: primary and secondary coverts of underwing.

- MOULT-CONTRAST: an obvious difference in colour and wear between adjacent feathers of different ages. A classic example occurs in adult breeding Common Terns, in which the contrast between newer paler inner primaries and older darker and more worn outer primaries on the upperwing forms a diagnostic field character.

- OUTERWING: primaries, primary coverts and alula.

- PRIMARY PROJECTION: on a folded wing, the distance primaries project beyond the longest tertial compared with the length of the exposed tertials.

- SADDLE: the mantle, back and scapulars together.

- SCAPULAR CRESCENT: narrow pale crescent formed by white tips of rearmost scapulars, often prominent on standing gull or tern.

- SECONDARY BAR: contrasting dark band on inner upperwing, formed by dark bases of secondaries.

- TAIL-STREAMERS: specialised rectrices (usually long and pointed) that project beyond other rectrices. Examples in this volume are tl of adult breeding jaegers and t6 of many terns.

- TERTIAL CRESCENT: narrow to broad pale crescent formed by white tips of longest tertials, often prominent on standing gull or tern.

- UNDERBODY: ventral body plumage, not including underwing and undertail.

- WING-POINT: in the Field Identification accounts, refers to that part of the wing-tip visible beyond the longest tertial on a folded wing; see also primary projection. For birds in the hand, refers to the longest primary on the folded wing.

REFERENCES

- Chandler, R.J . 1989. North Atlantic Shorebirds. MacMillan, Lond.

- Crome, F.J.H., & J. Shields. 1992. Parrots and Pigeons of Australia.

- Angus & Robertson, Sydney.

- Frith, H.J. 1982. Pigeons and Doves of Australia. Rigby, Sydney.

- Grant, P., & K. Mullarney. 1989. The New Approach to Identification. Peter Grant, Ashford, Kent, UK.

- Hayman, P., et al. 1986. Shorebirds. Croom Helm, Sydney.

- Harrison, P. 1983. Seabirds: An Identification Guide. Croom Helm,

- Lond.

- — 1987 Seabirds of the World: A Photographic Guide. Christopher

- Helm, Lond.

- Olsen, K.M., & H. Larsson. 1995. Terns of Europe and North

- America. Christopher Helm, Lond.

- Paulson, D. 1993. Shorebirds of the Pacific Northwest. Univ. Washington,

- Seattle.

- Pizzey, G. 1980. A Field Guide to the Birds of Australia. Collins,

- Sydney.

- Slater, P., et al. 1989. The Slater Field Guide to Australian Birds.

- Lansdowne Press, Sydney.

From Vol. 4

FIELD IDENTIFICATION

Generally, this section remains much as described in the Introduction to Volume 3, though we have changed the arrangement a little to try to remove further duplication between Field Identification and the sections of Plumages and related matters. The latter sections complement Field Identification and need to be consulted for detail on patterns of individual feathers and of moult. The first paragraph has been expanded to include the descriptions of field characters important in identification, ageing and sexing, concentrating on the overall appearance of the birds. The discussion of similar species also changes focus, from presenting details of the similar species to presenting those of the species under consideration. At times, where finer detail than is provided in the preceding description is required to distinguish similar species, such detail is usually given in the discussion of similar species, where comparisons can be directly made with the characters of the similar species.

HABITAT

[Information from Volumes 1 and 5]

From Vol. 1

The ideal habitat description for a particular species of bird presents an analysis of the critical factors determining distribution and the suitability of particular sites, taking into account needs for different purposes (e.g. feeding, breeding, roosting, moult); of the dynamics of use of habitat daily, seasonally or for longer periods; and of the effects of alteration of habitat, naturally or by human agency. It ought to apply throughout the species’ geographical range, or, at least, a large part of it. It ought to be predictive as well as descriptive and present possibilities and ideas for management.

By these criteria, there is scarcely a species within our region for which a comprehensive description of habitat can be compiled. The difficulties are the same as encountered in BWP and apply globally; particularly the lack of detailed studies for most species and the imprecise and inconsistent use of terms of description.

The most intractable difficulty is the lack of comprehensive studies on use of habitat by birds. This is a problem worldwide, but is exacerbated for us by low density of population, remoteness, inaccessibility and severe climatic conditions in some parts. In compiling these texts, the authors and editors have attempted to integrate and condense published information to produce a generalization for each species. For some species, we were fortunate to be able to draw on systematic studies. Also valuable were the observations and insights of experienced field observers. But all too often, in the absence of these sources, we gleaned information from numbers of short notes, papers on other topics, and annotated bird lists, much of it inevitably anecdotal, superficial and fragmentary. Even where there have been studies of habitat, often the focus is on aspects that are obvious or most amenable to study; for example, there is little quantitative information on use of airspace and underwater zones, and the study of the marine ecology of seabirds in our region is still in its infancy. Information from small areas is rarely interpreted with a view to integrating it into the wider geographical picture, and, perhaps most frustratingly, much valuable information remains unpublished or exists only in sources that are difficult to find.

Thus far, studies of avian habitats in our region have generated a bewildering variety of approaches to classification of habitat. The criteria used have in general been subjectively chosen, without evidence that they are relevant in determining the occurrence and abundance of birds, and many are appropriate only over small areas. Even where there are systems of classification covering wide areas and in widespread use in other disciplines, they have as yet received little attention from ornithologists e.g. Specht’s (1981) structural classification of vegetational formations in Aust.

In compiling this section, therefore, we have used terms for habitat description that are familiar and regularly used by both amateur and professional ornithologists, assigning to them reasonably precise meanings. Any more restrictive approach would exclude most information available at present. A glossary follows This presents terms used in the text that may be unfamiliar to some readers or that have other meanings in common usage in our region.

The Habitat section for each species discusses in sequence the biogeographical settings of distribution, broad terrestrial and aquatic groupings, details of habitats used for foraging, breeding, roosting and moulting, and relations with humans where these are pertinent. Although it is difficult to choose references for citation in a work such as this, we have attempted to provide primary sources, especially acknowledging sources of significant facts and studies of particular species or groups. It is impossible that such listings should be exhaustive. This work holds, with few exceptions, the first attempts to integrate all information available on habitat use by bird species using the A’asian and Antarctic regions. Probably the work’s most important function will be to stimulate further studies and encourage publication of existing information.

GLOSSARY

This glossary defines the principal terms used for habitat description in our text, in recognition of the need to standardize and increase the precision of such terms. A number of other terms are used throughout according to general English usage and are not defined here. References used in producing this compilation are Moore (1949), Press & Siever (1978), Corrick & Norman (1980), Gosper (1981), Pearce (1981), Specht (1981), Corrick (1982), Ainley & Boekelheide (1983), Ainley et al. (1984), McDonald et al. (1984), Aust. Atlas, and BWP.

- ACACIA SCRUB. Vegetation dominated by shrubs of the genus Acacia; includes open-scrub, tall shrubland, tall open-shrubland and low open-shrubland of Specht (1981).

- ANABRANCH (anastomosing plus branch). Branch that leaves river and re-enters it downstream.

- ANTARCTIC CONVERGENCE. See Polar Front.

- ANTARCTIC SLOPE FRONT. Oceanic zone overlying Antarctic continental slope, where shelf-water meets circumpolar deep water, and strong gradients of temperature, salinity and turbidity occur.

- AQUATIC VEGETATION. Plants growing in water; may reach but not project above surface.

- ARID ZONE. Regions where mean annual rainfall is less than 250 mm.

- ATOLL. Coral reef in the shape of a ring or horseshoe, broken or continuous; enclosing a lagoon.

- BACKWASH. Return flow of water down beach after wave has broken.

- BILLABONG. Properly an ox-bow lake, formed when a meander of a river is cut off as the river modifies its course; popularly used for other water-bodies.

- BORE. Hole drilled in the ground from which underground water is pumped and reticulated.

- BOUNDARY CURRENTS. Fast-flowing currents concentrated along edges of major oceans. Poleward currents on western edges of oceans are very intense and are known as WESTERN BOUNDARY CURRENTS.

- BRAIDED RIVER (STREAM). Intricate system of interlacing channels, formed in wide river-beds choked with coarse sediments.

- CAY. Flat mound of sand built up on reef flat slightly above high-tide level.

- CLEAR-FELLING. Forestry operation in which all trees on a site are cut down.

- CLIMATIC ZONES. GLOBAL. Five main zones into which Earth is divided according to climate. Comprise Tropical Zone: region lying between the Tropics of Cancer (23°27’N) and Capricorn (23°27’S); Frigid Zones: regions enclosed by Antarctic Circle (66°33’S) and Arctic Circle (66°33’N); Temperate Zones: regions lying between Tropical and Frigid Zones. MARINE. Climatic zones of oceanic surface water defined by Ainley & Boekelheide (1983). Tropical Zone: waters with sea surface-temperature (SST) of at least 22.0 °C. Subtropical Zone: SST 14.0-21.9 °C. Subantarctic Zone: SST 4.0—13.9 °C. Antarctic Zone: SST below 4.0 °C.

- CONTINENTAL SHELF. Underwater plateau extending from coast to a depth of about 200 m; shelf-waters: zone of water over the continental shelf.

- CONTINENTAL SLOPE. Beyond edge of continental shelf, ocean floor slopes to the abyssal plain (often at depths >4000 m). Worldwide, slope averages 4° but round Aust. may be up to 40° (Bunt 1987).

- CREEK. Stream of less volume than a river; small tidal channel through a coastal marsh; wide arm of a river or bay. Popularly applied in Aust. to any, rather small, drainage channel or waterway, permanent or impermanent, inland or coastal.

- DAM. Small (<10 ha), artificial water storage formed by excavation or impoundment; used for stock watering, irrigation or domestic supply in agricultural or pastoral regions.

- DRY SEASON. Season in monsoonal areas when little rain falls; usually Apr. to Nov. in ne. Aust.

- DUNE. Hill or ridge of sand formed by wind-blown sand or other granular material. CONSOLIDATED DUNE. Dune stabilized by cover of vegetation.

- EMERGENT VEGETATION. Plants projecting above canopy or water surface.

- EUTROPHICATION. Formation of superabundance of algal life in body of water, caused by influx of nutrients. FIORD. Former glacial valley with steep walls, now occupied by sea.

- FLOODPLAIN. Plain bordering a river; formed from sediments deposited during intermittent or seasonal flooding, and characterized by billabongs, swamps, meandering creeks.

- FOREST. Vegetation of trees, usually over 10 m high, with projective foliage cover of more than 50%; includes tall open-forest, open-forest and low open-forest of Specht (1981).

- FRONT (OCEANIC). Line or zone of separation at sea surface between water-masses of different physical characteristics, particularly temperature.

- GIBBER PLAIN. Level land covered with pebbles, usually in arid regions; little vegetation; barren stony waste.

- GUANO. Compacted mass of faeces of colonial species of birds; accumulated over many years.

- HEATH. Vegetation dominated by shrubs; includes closed-heathland, open-heathland and dwarf open-heathland of Specht (1981).

- HERB. Non-woody plant.

- ICE. Types discussed in the text are: SHELF-ICE: floating seaward extension of continental glaciers; SEA-ICE: ice formed by freezing of sea water; PACK-ICE: unattached sea-ice, varying from open to fully consolidated; FAST-ICE: sea-ice attached to shelf-ice or land; ICEBERG: mass of land-ice broken off from glacier and afloat at sea; ICE-FLOE: small mass of floating ice detached from pack-ice, limits usually within sight.

- IMPROVED PASTURE. Pasture to which fertilizer has been applied.

- ISLAND. Piece of land surrounded by water. Marine islands can be classified according to origin; CONTINENTAL ISLAND: formed by separation from continental mainland; OCEANIC ISLAND: formed in ocean independent of mainland; VOLCANIC ISLAND: volcanic in origin; CORAL ISLAND: built by action of coral polyps.

- ISOTHERM. Contour line joining points of equal temperature or equal average temperature; oceanic or atmospheric.

- KRILL. Marine crustaceans; Arthropoda, Crustacea, order Euphausiacea, Euphausia or Nyctiphanes. Form swarms in Antarctic and subantarctic seas.

- LAGOON. Strictly an enclosed coastal lake, pool or inlet, separated from ocean by broken or continuous banks of sand, earth or shingle; or waters enclosed by an atoll. In Aust. applied popularly to any rather shallow or small water-body such as billabong, pool or pond.

- LEVEE. Natural ridge along bank of creek or river formed by deposition of silt during flooding; also artificial barrier to floods constructed in similar form.

- LITTORAL. Intertidal area of sea or ocean.

- MALLEE. Multi-stemmed eucalypt growing from subterranean rhizome; also vegetation in which mallee is dominant; corresponds to open-scrub of Specht (1981).

- MANGROVE. Rhizophoraceae; many genera in Aust.

- MEADOW. Seasonal or transient shallow freshwater wetland characterized by cover of low emergent vegetation, particularly semi-aquatic herbs.

- MEANDER. Broad curves in creek or river forming as water erodes outer bank of curves and deposits sediment against inner bank.

- MONSOON. Climatic regime in which the wind blows in one direction for about half the year and in the opposite direction for the other half. Prominent in tropics on e. sides of continents; in ne. Aust., moist onshore winds prevail in summer.

- MONSOONAL REGIONS. Regions affected by the monsoon, and experiencing distinct wet and dry seasons. Within our limits, coastal and subcoastal ne. Aust. and adjacent islands.

- MORAINE. Deposit of debris and rock fragments at margin of glacier.

- PARK. Enclosed piece of public ground in urban areas, used for ornamental and recreational purposes; often planted with exotic grass, shrub and tree species, and containing artificial pools or lakes.

- POLAR FRONT. Circumpolar Zone where cold Antarctic surface-water sinks below less dense subantarctic surface-water; northernmost extent coincides with 2 °C subsurface isotherm.

- RAINFOREST. Dense forest growing in areas of heavy rainfall; trees are evergreen and predominantly broad-leaved; includes tall closed-forest, closed-forest, low closed-forest and closed-shrub of Specht (1981).

- REED. Herbaceous erect plant, particularly of the genus Phragmites.

- REEF. Ridge of rock or coral (CORAL REEF) in sea, just above or below the surface. RIP. Narrow, fast-flowing ocean current. RUSH. Herbaceous erect plant of the families Juncaceae, Typhaceae.

- SALT LAKE. Lake, usually in arid or semi-arid zone, where evaporation exceeds inflow, so that water highly saline; in arid Aust., usually dry with flat barren surface-deposit of salt.

- SALTBUSH. Vegetation in which chenopods are dominant, particularly Atriplex, Enchylaena, Rhagodia ; includes low-shrubland, low open-shrubland and very open sedgeland of Specht (1981).

- SALTFIELD. Set of ponds for production of salt by natural evaporation of seawater.

- SALTMARSH. Low-lying, flat land regularly or intermittently flooded by saline or brackish water and covered or fringed by halophytic vegetation; coastal or inland.

- SALTPAN. Semi-permanent saline wetland; some aquatic plants (e.g. Ruppia, Lepilaena) in shallow waters; little or no emergent vegetation.

- SCORIA. Congealed lava or lava fragments containing large number of vesicles.

- SCREE. See TALUS.

- SEAMOUNT. Submarine mountain rising at least 900 m above ocean floor.

- SEDGE. Herbaceous erect plant; Cyperaceae and some other families.

- SEMLARID ZONE. Regions with mean annual rainfall of 250–500 mm.

- SHRUB. Woody plant <8 m tall, with many branches and ample foliage; replaces BWP’s BUSH; in common usage in Aust. for remote or undeveloped country.

- SPINIFEX. Vegetational association in which mound-forming grasses, known collectively as spinifex, are dominant; Gramineae, Triodia and Plechtrachne.

- STACK. Rocky islet or pillar near coastline, isolated by erosive action of waves.

- SWAMP. Wetland area, permanent, seasonal or ephemeral; typically richly vegetated with emergent and aquatic plants. BWP classifies vegetated wetlands as MARSHES and SWAMPS on the basis of persistence of water, but the dry climate over much of our region ensures that few wetlands, shallow enough to support rich plant growth, are permanent.

- TALUS. Deposit of angular fragments of weathered rock accumulated at base of cliff or steep slope.

- TUSSOCK GRASSLAND. Grassland dominated by grasses forming discrete but open tussocks.

- UNDERSTOREY. Shrub or tree layer below uppermost stratum.

- VOLCANO. Vent in earth’s crust through which lava reaches surface; includes deposits surrounding vent.

- VOLCANIC ASH. Fine particles of lava ejected from volcano in eruption and deposited as sediment on land.

- VOLCANIC OR CINDER CONE. Conical hill built up of material ejected from volcano and deposited around outlet.

- WET SEASON. Season in monsoonal areas when most rain falls; usually Dec.—Mar. in ne. Aust.

- WOODLAND. Vegetation association of well-spaced trees less than 30m high; includes open-forest, low open-forest, woodland, low woodland, open-woodland and low open-woodland of Specht (1981).

REFERENCES

- Ainley, D.G., & R.J. Boekelheide. 1983. Studies avian Biol. 8: 2-23.

- Ainley, D.G., et al. 1984. AOU orn. Monogr. 32: 1-97.

- Bunt, J.S. 1987. Pp. 17-42. In Fauna of Australia. 1A.

- Corrick, A.H. 1982. Proc. R. Soc. Vict. 94: 69-87.

- Corrick, A.H., & F.I. Norman. 1980. Proc. R. Soc. Vict. 91: 1-15.

- Gosper, D.G. 1981. Corella 5: 1-18.

- Keast, A. (Ed) 1981. Ecological Biogeography of Australia.

- McDonald, R.C., et al. 1984. Australian Soil and Land Survey Field Handbook.

- Moore, W.G. 1949. A Dictionary of Geography.

- Pearce, A. 1981. CSIRO Div. Fish. Oceanogr. Rep. 132: 1-51.

- Press, F., & R. Siever. 1978. Earth.

- Specht, R.L. 1981. Pp 163-297. In: Keast 1981.

From Vol. 5

The problems in assembling the habitat texts were discussed in the introduction to Volume 1 and have proved to be common to all subsequent volumes. For nearly all of the species in the HANZAB region that we have dealt with so far, it has proved difficult, and sometimes impossible, to assemble even a general overview of use of habitat by birds, let alone an analysis of the critical variables of habitat for each species. There are few comprehensive studies on habitat use by birds in the region and the texts in HANZAB are, for most species, the first attempt at collating and synthesizing the diversity of information contained in a wide range of published and unpublished sources.

In addition to the lack of systematic study and analysis of habitat, the difficulty of assembling an overview of habitat use by birds in the HANZAB region is exacerbated by the lack of consistent, or even accurate, classification of habitats by both amateur and professional ornithologists. While this is understandable in early literature, it is disappointing to find this perpetuated in more recent systematic studies or annotated lists, especially given the availability of systems of habitat classification covering wide areas and in widespread use in other disciplines, e.g. Specht’s (1981) structural classification of vegetation formations in Aust. Happily, there are increasing numbers of studies that do adopt accepted systematic classifications of vegetation and other habitat variables.

Despite the problems just described, we have attempted to describe habitat with standard terms. For structural descriptions of rainforest and non-rainforest vegetation and descriptions of landforms, we have as far as possible used the definitions given in the Australian Soil and Land Survey Field Handbook (McDonald et al. 1984; also see AUSLIG 1990). Other terms we use commonly are given in the glossary associated with the introduction to Habitat in Volume 1 (and which is not repeated here). Equally, however, it is not always possible to convert the often vague and ill-defined descriptions found in the published literature (e.g. scrub) to standard terminology; where it is considered useful, we include such descriptions, usually without comment.

Given our experience in assembling habitat texts for this and previous volumes, particularly when dealing with the primarily terrestrial species of Volume 4 and the passerine volumes here and to come, we have changed the arrangement of this section. Previously, following the first paragraph, there were separate paragraphs that dealt with breeding, feeding and roosting and loafing habitats. These paragraphs have been abandoned in this and subsequent volumes because:

- such habitats are almost always the same as those already described in the preceding paragraphs or, occasionally, a subset of them; and

- because we usually have so few details of such habitats beyond some details of use of sites for these behaviours, and which are already summarized in Breeding (Site), Food (Behaviour) and Social Behaviour (Roosting).

Finally, the information concerning human interactions and modifications to habitat, formerly in the last paragraph, has been moved to a new section, Threats and Human Interactions (see below).

The usual arrangement in this and remaining volumes is as follows. Unless there is very little information in total, the section opens with a brief introductory paragraph that summarizes: the main habitat types used by the species; the biogeographical settings of distribution, identifying the climatic zones in which the species occurs; and, if there is information available, the commonly inhabited landforms in which the species occurs. General references are provided here, but the references provided in the following more detailed analysis must also be consulted for a complete listing.

The introductory paragraph is then followed by a synthesis of the available information on use of habitat by the species, dealing firstly with those habitats used most often or commonly, through to those used only infrequently. Use of modified habitats (such as urban areas or farmland) is also discussed, either separately at the end of the paragraph, or integrated with the main discussion, depending on the frequency of use of such habitats. Occasionally, information is presented separately for different subspecies or different biogeographical or climatic regions (e.g. for widespread species ). We have tried to cite all important primary sources, especially acknowledging sources of significant facts and studies of particular species or groups. It is impossible that such listings of references should be exhaustive. Lastly, where there are detailed studies, these are often now presented in a separate final paragraph and may include information on differential use of habitats in an area or region or details of studies of human impacts, such as fire or logging.

REFERENCES

- AUSLIG. 1990. Atlas of Australian Resources. 6. Vegetation. Third series. Aust. Surveying & Land Information Grp, Dept Administrative Services, Canberra.

- Keast, A. (Ed.) 1981. Ecological Biogeography of Australia. Junk, The Hague.

- McDonald, R.C., et al. 1984. Australian Soil and Land Survey Field Handbook. Inkata Press, Melbourne.

- Specht, R.L. 198 1. Pp 163-297 In: Keast 1981.

DISTRIBUTION AND POPULATION

[Information from Volumes 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7

From Vol. 1

In this section we try to present a summary of the known distribution of each species, within our limits with a mention of extralimital range. Maps of distribution appear for all species except accidental vagrants and, like good cartoons, obviate the need for much text. However, they can be presented only on a small scale and so some fairly detailed explanation has to be appended to make them useful. Distribution is inextricably linked with movements though we try and avoid overlap with that section.

After a summary of world distribution of the species and its occurrence in our region, details of distribution are given, generally for Aust., NZ, the territories of Lord Howe, Norfolk, Christmas and Cocos-Keeling, Kermadec and Chatham Is, in that order, followed by records in subantarctic islands and vagrants elsewhere. For Antarctic and pelagic species, the main distribution is usually given first and then records in more temperate regions in the same order as above. Breeding distribution is then considered. The last paragraphs give estimates of population (if not already with breeding distribution), and the status of the species. The history of introductions and colonizations is outlined where necessary.

Breeding distribution and Population

It hardly needs saying that, as regards the speciation and classification of birds, a vital consideration is interbreeding with accompanying gene-flow. One assumes that this takes place only within the breeding range. It is on the basis of breeding range that the question of sympatry or allopatry is established. Thus, the breeding range of a species is surely what is fundamentally important from a biological point of view. However, there is surprisingly little information on the present breeding range of many A’asian species. Within Aust. it may be thought that the Atlas of Australian Birds and RAOU Nest Record Scheme would meet requirements, but the Atlas relied primarily on records of presence or absence, and evidence for breeding came a poor second. Records in the NRS are usually too scattered and fragmentary to be of much use. In consequence, one has no means of knowing whether breeding occurs in all blocks where the birds were seen during the Atlas work, though one may be quite certain that it did not do so. Later work, such as organized waterbird surveys in Vic. and WA, has enabled us to fill some gaps. For NZ, the situation is even worse because the Atlas of New Zealand Birds does not indicate breeding. For most colonially nesting species, each colony known to us is listed, with its size in recent years. However, for some species, such as ibises, only the larger or long-established colonies are listed, with references to sources. The estimated figures may or may not give a reasonable idea of populations at the present time. They ought, however, to provide a measure against which future fluctuations can be judged. They ought also to encourage people to fill the gaps that must be there. Similarly, figures of recent surveys of waterfowl are recorded, as an index of the numbers of birds seen rather than as actual censuses. All the same, there are no estimates of populations for many species.

Accidental and vagrant species. First records for species in Aust. and NZ, records of a species far outside its normal range and records of vagrants generally present difficulties. It is no use burking this question, and the fact is that, until recently, reporting and vetting of such records in Aust. has been deplorable. Until recently, there has been no official body to which records have to be submitted for critical appraisal and acceptance before publication. In consequence, publication has often been made without any acceptable supporting justification and acceptance has been lax. Indeed, we have found that some such records accepted in the Atlas of Australian Birds are not acceptable by modern standards.

In 1975 the RAOU established the Records Appraisal Committee for reviewing unusual records of all sorts. Unfortunately, for many reasons, the Committee has vetted few records and has not yet achieved much authority. The Committee has been reformed and is now evaluating published and unpublished records. At the same time, within the last 20 years or so, the standard of exact and critical observation in the field has been improved immensely by the enthusiasm and abilities of a new generation of field observers, particularly as regards waders and seabirds, and by the organizing of regular boat-trips across the continental shelf. In this way, a great deal of valuable information on occurrence, status and distribution of species hitherto little known in our region has accumulated, but unhappily not much of it has been published satisfactorily. This is fair neither to the observers, who have not received their due credit, nor to general ornithologists, who have to accept the observations on hearsay or not at all. In a work that is trying to assemble the facts, the situation is unsatisfactory at best, impossible at worst. In various ways, we have tried to compromise by allowing that there is knowledge beyond our reach, while recording only acceptable fact. As far as possible, we give references to the original source for all vav grant and unusual records and comment on their acceptability.

Maps

Distribution for each species is shown on one, or more, of the following maps: World, Polar, Aust. and NZ, Aust., NZ, or Tas. We usually present the minimum number of maps in each account: for example, if a species occurs only in NZ, then only that one map is used. However, for many species, distribution (including extralimital range) is shown on a world map and, in more detail on, say, the Aust. and NZ map. All maps have breeding and non-breeding distribution shown in the same manner: breeding distribution is coloured full red. Areas where birds are recorded without known breeding are coloured half-tone red. Vagrant records far from any area of usual occurrence are simply small half-tone red dots or arrows. For islands, and sections of the coast of Antarctica and some coasts elsewhere, breeding and non-breeding are indicated by full red and half-tone red arrows respectively. For seabirds, distribution at sea is in half-tone red without separation into summer and winter or breeding or non-breeding ranges because so little is known of that matter for most species. Where differences between summer and winter range are known it is discussed in the text on distribution or movements rather than shown on a map.

One of the chief difficulties has been to distinguish between breeding and non-breeding ranges, at any rate for species of Aust. and NZ landbirds (see above). When mapping breeding distribution, where ought the lines to be drawn? This can only be a matter of personal judgement, and each person’s judgement will differ. As a general rule, we have tried to outline those areas, based on Atlas blocks, in which the Atlas and other data record breeding as having occurred in the recent past, usually in the past two decades. These areas are coloured full red and include any isolated blocks where breeding was not recorded that are inliers in such areas. The uncertainties of the presentations ought to encourage and give scope to observers to find us at fault.

Movements also were a problem. For species dealt with in this volume, simple migration between breeding and non-breeding areas either does not take place in a clearly defined seasonal manner in our region, except for a few procellariiforms, or movements that do take place are not well enough understood to depict. In short, for the species in Volume 1, it is hardly feasible to present the vagaries of such movement in a succinct form and they are not indicated on maps of distribution.

Much of the information in this section comes from bird reports published in Aust. or NZ. For NZ, annual reports of unusual or interesting records are published as Classified Summarised Notes in Notornis. In Aust., there is no national bird report. However, most States publish or have published bird reports and Corella (formerly Australian Bird Bander) continues to publish accounts of breeding birds in its Seabird Islands Series. These references have generally been abbreviated as follows; each is followed by the year of the report (not the year of publication) except for CSN, which is followed by the volume of Notornis in which it is found.

| Report | Published in or by | |

|---|---|---|

| Qld Bird Rep. | Sunbird (Qld Orn. Soc.) | |

| NSW Bird Rep. | Aust. Birds (NSW Field Orn. Club) (formerly Birds) | |

| Vic. Bird Rep. | Bird Observer’s Club of Australia | |

| Tas. Bird Rep. | Tasmanian Bird Report (Bird Obs. Assoc. Tas.) | |

| SA Bird Rep. | S. Aust. Orn. (SA Orn. Assoc.) | |

| WA Bird Rep. | WA Group of the RAOU | |

| CSN | Notornis (OSNZ) | |

From Vol. 2

The breeding range of a species is the most biologically important part of its total distribution. However, for most species in our region, the limits of breeding and non-breeding distribution are not well known. For many pelagic and colonially nesting species, breeding ranges are often quite well, or even exactly, known but non-breeding ranges are often a total mystery. For terrestrial birds, general occurrence or range may usually be fairly assessed but breeding range and localities are often poorly known.

In compiling texts and maps, a great many sources are used. For species occurring in Aust. and NZ, The Atlas of Australian Birds and Atlas of Bird Distribution in New Zealand formed the basis of most accounts, which were supplemented with information from literature published after the atlases and other, unpublished, sources. Annual bird reports were a valuable source of information on local rarities, expansion of range, annual fluctuations in general abundance, and movements.

The Atlases are fundamentally flawed as regards breeding range and are uncertain and inexact guides because observers were not specifically asked or obliged to search for or record evidence of breeding. Thus, one cannot assess the significance of a breeding record or lack of one in an Atlas block. Is a record of breeding a chance sighting of one nest in five years or records of several nests each year? Similarly, a blank block, or one showing occurrence only, does not necessarily mean that breeding does not take place there, only that it was not recorded because the area was visited only in the non-breeding season, or suitable habitat was not investigated, or for other reasons.

Maps

Presentation of the maps remains as in Volume 1, with breeding areas shown in full red and areas of occurrence where breeding has not been recorded in half-tone red. The maps are gross approximations simply because their scale is so small. The limits of different areas are no more precise on our maps than they are on others, such as those in field guides, though it may be easier to place those limits in relation to towns and well -known localities.

In this Volume we have used a map that shows New Guinea, central and e. Indonesia and some islands of the sw. Pacific Ocean with Aust., or with Aust. and NZ. This obviates the need for a world map for species that occur within the HANZAB region but are also only recorded in parts of New Guinea or Indonesia. However, because we know little of the limits of breeding and non-breeding distribution of species in New Guinea and Indonesia, on these maps distribution has usually been shown in halftone red, giving no indication of breeding range outside the HANZAB region.

From Vol. 3

Vagrant species For species new to Australia and its territories or species listed on the Review List of the RAOU’s Record Appraisal Committee (RAC), non-specimen records must be vetted and accepted by the RAC before a species is included on the Australian list or before a record is considered valid. However, the RAC does not review published records unless they have been submitted to them independently. This creates problems with sight-records published before the establishment of the RAC, which, by and large, have not been

vetted.

We have usually listed as acceptable only those sight- or sound-records that have been accepted by the RAC. However, records of species on the Review List but published before the establishment of the RAC and that include an adequate description of a species are usually listed as acceptable. All early sight-records without description and all sight-records since the establishment of the RAC that have not been submitted to the RAC are listed as unverified or unacceptable.

Many unverified reports of rare or vagrant species are published in the RAOU Newsletter (till Dec. 1990) or Wingspan (in Twitcher’s Corner), or in OSNZ News. These must be considered unacceptable records until they have been submitted to the RAC (Aust.), Rare Birds Committee (RBC; NZ) or relevant State authority. In the accounts these are usually listed as ‘unverified’, without reference. In Aust., records in State bird reports are accepted except for species on the RAC Review List.

Populations

In the Charadriiformes, the estimated total Aust. population for each species is taken from Watkins (1993). We have also included the results of long-term surveys conducted in Aust. and NZ. In Aust., regular counts are usually only a small proportion of the estimated total population. However, we have included these data to show annual variation in numbers in Aust., which, for at least some species, reflects breeding success.

Unlike earlier volumes, Christmas I. refers to the Australian territory in the Indian Ocean unless followed by ‘(Pac.)’, which then indicates the island in the central Pacific Ocean.

Maps

Presentation of maps remains as in Volume 2, with breeding areas shown in full red and areas of occurrence where breeding has not been recorded in half-tone red. Because we know little of the limits of breeding and non-breeding distribution of species in New Guinea and Indonesia, distribution in these regions has usually been shown in half-tone red, giving no indication of breeding range outside the HANZAB region. [this paragraph repeated in Volume 4]

REFERENCES

- Watkins, O. 1993. RAOU Rep. 90.

From Vol. 5

The detailed descriptions of distribution need to be read in conjunction with the maps, which themselves obviate the need for much text. Because the maps can be presented at only a small scale, the text describes the mapped distribution of each species state by state or regionally, indicating whether the species is widespread throughout that range, scattered or patchily distributed; and gaps or continuities in distribution that may not be obvious from the maps are discussed.

The breeding range of a species is the most biologically important part of its total distribution yet for most species in the HANZAB region one of the chief difficulties in assembling both texts and maps is to distinguish between breeding and non-breeding ranges. For most terrestrial species of Aust. and NZ, general occurrence or range may usually be fairly assessed but breeding distribution and localities are often poorly known, even for colonially breeding species. The discussion of breeding distribution relies on the map and the preceding discussion of overall distribution.

In compiling text and maps, a great many sources are used. For species occurring in Aust. and NZ, The Atlas of Australian Birds (Blakers et al. 1984) or The Atlas of Bird Distribution in New Zealand (Bull et al. 1985) form the basis for discussing and presenting both breeding and non-breeding ranges in the text and the maps. These known ranges are supplemented by records published since then (of special note are the Atlas of Victorian Birds [Emison et al. 1987] and Birds of the Australian Capital Territory. An Atlas [Taylor & COG 1992]), some unpublished records and, for Aust., data from the NRS. Annual bird reports for a variety of regions or states are a valuable source of information on local rarities, changes in range, annual fluctuations in general abundance, irruptions, and movements.

However, for Aust., The Atlas of Australian Birds is an imperfect record of breeding distribution because observers were not required to search for, or even submit, evidence of breeding (though it was encouraged); and many areas beyond the well-populated e. coast, SE and SW remained little visited; some areas may never have been visited for more than a few hours and not certainly when breeding may have occurred or in breeding habitat of a species within that block. Thus it is difficult to assess the significance of a breeding record or the lack of one in the Atlas. For all that, however, the Atlas remains the best record of breeding and no n -breeding distribution in Aust. Combined with other sources, the text and maps are thus records of known non-breeding and breeding distribution, though for all but a few species they remain an incomplete record of these ranges. By taking the approach we have we hope to stimulate observation of breeding range and publication of such observations to fill the all-too-obvious gaps in our knowledge. The New Atlas of Australian Birds currently underway

should also provide much useful information.

For NZ, The Atlas of Bird Distribution in New Zealand (Bull et al. 1985) did not distinguish breeding distribution on the maps, stating that ‘apart from pelagic species and migrant waders, most New Zealand species breed throughout their ranges and the exceptions are noted with the relevant maps’. Records of breeding are, however, summarized for each grid square in a microfiche appendix to the Atlas. The NZ Atlas suffers the same problems as the Aust. Atlas regarding recording of breeding distribution. Thus, breeding distribution for NZ is determined from published descriptions and records, and the microfiche records of the NZ Atlas.

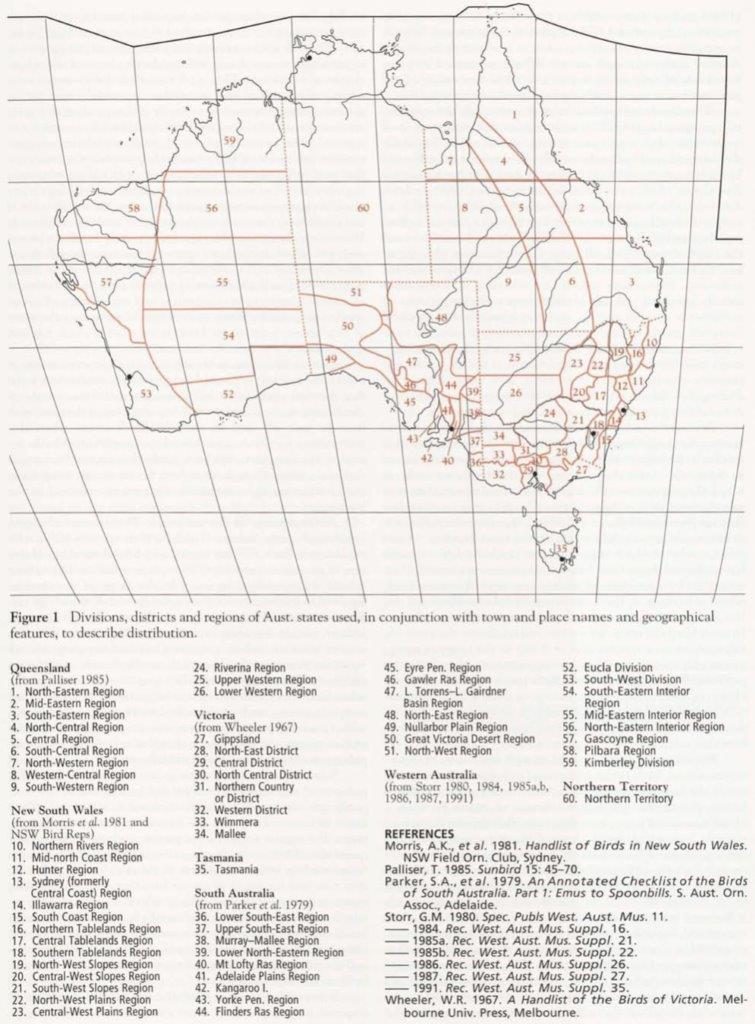

Figure 1 shows the regions, divisions and districts of the various Aust. states that are used in conjunction with town and place names and geographical features to describe distribution. The end-paper map for NZ (inside rear cover [see Gazeteer]) shows the regions of the main islands which are used to describe distribution there.

Vagrant and rare species

For species new to Aust. and its territories or species listed on the Review List of the Birds Australia Rarities Committee (BARC, which was formerly the RAOU Records Appraisal Committee [RAC]) , non-specimen records must be vetted and accepted by BARC before a species is included on the Aust. list or before a record is considered valid (see Palliser 1999 and Palliser & Eades 2000 for a copy of the Review List and the role of BARC). However, BARC does not review published records unless they have been submitted to them independently. This creates problems with sight records published before the establishment of BARC or, before that, the RAC, which, by and large, have not been vetted.